2. Variables, expressions and statements¶

2.1. Values and data types¶

A value is one of the fundamental things — like a letter or a number — that a program manipulates. The values we have seen so far are 4 (the result when we added 2 + 2), and "Hello, World!".

These values are classified into different classes, or data types: 4 is an integer, and "Hello, World!" is a string, so-called because it contains a string of letters. You (and the interpreter) can identify strings because they are enclosed in quotation marks.

If you are not sure what class a value falls into, Python has a function called type which can tell you.

>>> type("Hello, World!")

<class 'str'>

>>> type(17)

<class 'int'>

Not surprisingly, strings belong to the class str and integers belong to the class int. Less obviously, numbers with a decimal point belong to a class called float, because these numbers are represented in a format called floating-point. At this stage, you can treat the words class and type interchangeably. We’ll come back to a deeper understanding of what a class is in later chapters.

>>> type(3.2)

<class 'float'>

What about values like "17" and "3.2"? They look like numbers, but they are in quotation marks like strings.

>>> type("17")

<class 'str'>

>>> type("3.2")

<class 'str'>

They’re strings!

Strings in Python can be enclosed in either single quotes (') or double quotes ("), or three of each (''' or """)

>>> type('This is a string.')

<class 'str'>

>>> type("And so is this.")

<class 'str'>

>>> type("""and this.""")

<class 'str'>

>>> type('''and even this...''')

<class 'str'>

Double quoted strings can contain single quotes inside them, as in "Bruce's beard", and single quoted strings can have double quotes inside them, as in 'The knights who say "Ni!"'.

Strings enclosed with three occurrences of either quote symbol are called triple quoted strings. They can contain either single or double quotes:

>>> print('''"Oh no", she exclaimed, "Ben's bike is broken!"''')

"Oh no", she exclaimed, "Ben's bike is broken!"

>>>

Triple quoted strings can even span multiple lines:

>>> message = """This message will

... span several

... lines."""

>>> print(message)

This message will

span several

lines.

>>>

Python doesn’t care whether you use single or double quotes or the three-of-a-kind quotes to surround your strings: once it has parsed the text of your program or command, the way it stores the value is identical in all cases, and the surrounding quotes are not part of the value. But when the interpreter wants to display a string, it has to decide which quotes to use to make it look like a string.

>>> 'This is a string.'

'This is a string.'

>>> """And so is this."""

'And so is this.'

So the Python language designers usually chose to surround their strings by single quotes. What do think would happen if the string already contained single quotes? Try it for yourself and see.

When you type a large integer, you might be tempted to use commas between groups of three digits, as in 42,000. This is not a legal integer in Python, but it does mean something else, which is legal:

>>> 42000

42000

>>> 42,000

(42, 0)

Well, that’s not what we expected at all! Because of the comma, Python chose to treat this as a pair of values. We’ll come back to learn about pairs later. But, for the moment, remember not to put commas or spaces in your integers, no matter how big they are. Also revisit what we said in the previous chapter: formal languages are strict, the notation is concise, and even the smallest change might mean something quite different from what you intended.

2.2. Variables¶

One of the most powerful features of a programming language is the ability to manipulate variables. A variable is a name that refers to a value.

Assignment statements create new variables and give them values:

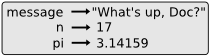

>>> message = "What's up, Doc?"

>>> n = 17

>>> pi = 3.14159

This example makes three assignments. The first assigns the string value "What's up, Doc?" to a new variable named message. The second gives the integer 17 to n, and the third assigns the floating-point number 3.14159 to a variable called pi.

The assignment token, =, should not be confused with equals, which uses the token ==. The assignment statement links a name, on the left hand side of the operator, with a value, on the right hand side. This is why you will get an error if you enter:

>>> 17 = n

Tip

When reading or writing code, say to yourself “n is assigned 17” or “n gets the value 17”. Don’t say “n equals 17”.

Note

In case you are wondering, a token is a character or string of characters that has syntactic meaning in a language. In Python operators, keywords, literals, and white space all form tokens in the language.

A common way to represent variables on paper is to write the name with an arrow pointing to the variable’s value. This kind of figure is called a state snapshot because it shows what state each of the variables is in at a particular instant in time. (Think of it as the variable’s state of mind). This diagram shows the result of executing the assignment statements:

If you ask the interpreter to evaluate a variable, it will produce the value that is currently linked to the variable:

>>> message

'What's up, Doc?'

>>> n

17

>>> pi

3.14159

In each case the result is the value of the variable. Variables also have types; again, we can ask the interpreter what they are.

>>> type(message)

<class 'str'>

>>> type(n)

<class 'int'>

>>> type(pi)

<class 'float'>

The type of a variable is the type of the value it currently refers to.

We use variables in a program to “remember” things, like the current score at the football game. But variables are variable. This means they can change over time, just like the scoreboard at a football game. You can assign a value to a variable, and later assign a different value to the same variable.

Note

This is different from math. In math, if you give x the value 3, it cannot change to link to a different value half-way through your calculations!

>>> day = "Thursday"

>>> day

'Thursday'

>>> day = "Friday"

>>> day

'Friday'

>>> day = 21

>>> day

21

You’ll notice we changed the value of day three times, and on the third assignment we even gave it a value that was of a different type.

A great deal of programming is about having the computer remember things, e.g. The number of missed calls on your phone, and then arranging to update or change the variable when you miss another call.

2.3. Variable names and keywords¶

Valid variable names in Python must conform to the following three simple rules:

- They are an arbitrarily long sequence of letters and digits.

- The sequence must begin with a letter.

- In addtion to a..z, and A..Z, the underscore (_) is a letter.

Although it is legal to use uppercase letters, by convention we don’t. If you do, remember that case matters. Bruce and bruce are different variables.

The underscore character ( _) can appear in a name. It is often used in names with multiple words, such as my_name or price_of_tea_in_china.

There are some situations in which names beginning with an underscore have special meaning, so a safe rule for beginners is to start all names with a letter other than the underscore.

If you give a variable an illegal name, you get a syntax error:

>>> 76trombones = "big parade"

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> more$ = 1000000

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> class = "Computer Science 101"

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

76trombones is illegal because it does not begin with a letter. more$ is illegal because it contains an illegal character, the dollar sign. But what’s wrong with class?

It turns out that class is one of the Python keywords. Keywords define the language’s syntax rules and structure, and they cannot be used as variable names.

Python has thirty-something keywords (and every now and again improvements to Python introduce or eliminate one or two):

| and | as | assert | break | class | continue |

| def | del | elif | else | except | exec |

| finally | for | from | global | if | import |

| in | is | lambda | nonlocal | not | or |

| pass | raise | return | try | while | with |

| yield | True | False | None |

You might want to keep this list handy. If the interpreter complains about one of your variable names and you don’t know why, see if it is on this list.

Programmers generally choose names for their variables that are meaningful to the human readers of the program — they help the programmer document, or remember, what the variable is used for.

Caution

Beginners sometimes confuse “meaningful to the human readers” with “meaningful to the computer”. So they’ll wrongly think that because they’ve called some variable average or pi, it will somehow automagically calculate an average, or automagically associate the variable pi with the value 3.14159. No! The computer doesn’t attach semantic meaning to your variable names.

So you’ll find some instructors who deliberately don’t choose meaningful names when they teach beginners — not because they don’t think it is a good habit, but because they’re trying to reinforce the message that you, the programmer, have to write some program code to calculate the average, or you must write an assignment statement to give a variable the value you want it to have.

2.4. Statements¶

A statement is an instruction that the Python interpreter can execute. We have only seen the assignment statement so far. Some other kinds of statements that we’ll see shortly are while statements, for statements, if statements, and import statements. (There are other kinds too!)

When you type a statement on the command line, Python executes it. Statements don’t produce any result.

2.5. Evaluating expressions¶

An expression is a combination of values, variables, operators, and calls to functions. If you type an expression at the Python prompt, the interpreter evaluates it and displays the result:

>>> 1 + 1

2

>>> len("hello")

5

In this example len is a built-in Python function that returns the number of characters in a string. We’ve previously seen the print and the type functions, so this is our third example of a function!

The evaluation of an expression produces a value, which is why expressions can appear on the right hand side of assignment statements. A value all by itself is a simple expression, and so is a variable.

>>> 17

17

>>> y = 3.14

>>> x = len("hello")

>>> x

5

>>> y

3.14

2.6. Operators and operands¶

Operators are special tokens that represent computations like addition, multiplication and division. The values the operator uses are called operands.

The following are all legal Python expressions whose meaning is more or less clear:

20 + 32 hour - 1 hour * 60 + minute minute / 60 5 ** 2

(5 + 9) * (15 - 7)

The tokens +, -, and *, and the use of parenthesis for grouping, mean in Python what they mean in mathematics. The asterisk (*) is the token for multiplication, and ** is the token for exponentiation.

>>> 2 ** 3

8

>>> 3 ** 2

9

When a variable name appears in the place of an operand, it is replaced with its value before the operation is performed.

Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and exponentiation all do what you expect.

Example: so let us convert 645 minutes into hours:

>>> minutes = 645

>>> hours = minutes / 60

>>> hours

10.75

Oops! In Python 3, the division operator / always yields a floating point result. What we might have wanted to know was how many whole hours there are, and how many minutes remain. Python gives us two different flavours of the division operator. The second, called integer division uses the token //. It always truncates its result down to the next smallest integer (to the left on the number line).

>>> 7 / 4

1.75

>>> 7 // 4

1

>>> minutes = 645

>>> hours = minutes // 60

>>> hours

10

Take care that you choose the correct falvour of the division operator. If you’re working with expressions where you need floating point values, use the division operator that does the division accurately.

2.7. Type converter functions¶

Here we’ll look at three more Python functions, int, float and str, which will (attempt to) convert their arguments into types int, float and str respectively. We call these type converter functions.

The int function can take a floating point number or a string, and turn it into an int. For floating point numbers, it discards the decimal portion of the number - a process we call truncation towards zero on the number line. Let us see this in action:

>>> int(3.14)

3

>>> int(3.9999) # This doesn't round to the closest int!

3

>>> int(3.0)

3

>>> int(-3.999) # Note that the result is closer to zero

-3

>>> int(minutes/60)

10

>>> int("2345") # parse a string to produce an int

2345

>>> int(17) # int even works if its argument is already an int

17

>>> int("23 bottles")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<interactive input>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: '23 bottles'

The last case shows that a string has to be a syntactically legal number, otherwise you’ll get one of those pesky runtime errors.

The type converter float can turn an integer, a float, or a syntactically legal string into a float.

>>> float(17)

17.0

>>> float("123.45")

123.45

The type converter str turns its argument into a string:

>>> str(17)

'17'

>>> str(123.45)

'123.45'

2.8. Order of operations¶

When more than one operator appears in an expression, the order of evaluation depends on the rules of precedence. Python follows the same precedence rules for its mathematical operators that mathematics does. The acronym PEMDAS is a useful way to remember the order of operations:

- Parentheses have the highest precedence and can be used to force an expression to evaluate in the order you want. Since expressions in parentheses are evaluated first, 2 * (3-1) is 4, and (1+1)**(5-2) is 8. You can also use parentheses to make an expression easier to read, as in (minute * 100) / 60, even though it doesn’t change the result.

- Exponentiation has the next highest precedence, so 2**1+1 is 3 and not 4, and 3*1**3 is 3 and not 27.

- Multiplication and both Division operators have the same precedence, which is higher than Addition and Subtraction, which also have the same precedence. So 2*3-1 yields 5 rather than 4, and 5-2*2 is 1, not 6. #. Operators with the same precedence are evaluated from left-to-right. In algebra we say they are left-associative. So in the expression 6-3+2, the subtraction happens first, yielding 3. We then add 2 to get the result 5. If the operations had been evaluated from right to left, the result would have been 6-(3+2), which is 1. (The acronym PEDMAS could mislead you to thinking that division has higher precedence than multiplication, and addition is done ahead of subtraction - don’t be misled. Subtraction and addition are at the same precedence, and the left-to-right rule applies.)

Note

Due to some historical quirk, an exception to the left-to-right left-associative rule is the exponentiation operator **, so a useful hint is to always use parentheses to force exactly the order you want when exponentiation is involved:

>>> 2 ** 3 ** 2 # the right-most ** operator gets done first!

512

>>> (2 ** 3) ** 2 # use parentheses to force the order you want!

64

The immediate mode command prompt of Python is great for exploring and experimenting with expressions like this.

2.9. Operations on strings¶

In general, you cannot perform mathematical operations on strings, even if the strings look like numbers. The following are illegal (assuming that message has type string):

message - 1 "Hello" / 123 message * "Hello" "15" + 2

Interestingly, the + operator does work with strings, but for strings, the + operator represents concatenation, not addition. Concatenation means joining the two operands by linking them end-to-end. For example:

fruit = "banana"

baked_good = " nut bread"

print(fruit + baked_good)

The output of this program is banana nut bread. The space before the word nut is part of the string, and is necessary to produce the space between the concatenated strings.

The * operator also works on strings; it performs repetition. For example, 'Fun'*3 is 'FunFunFun'. One of the operands has to be a string; the other has to be an integer.

On one hand, this interpretation of + and * makes sense by analogy with addition and multiplication. Just as 4*3 is equivalent to 4+4+4, we expect "Fun"*3 to be the same as "Fun"+"Fun"+"Fun", and it is. On the other hand, there is a significant way in which string concatenation and repetition are different from integer addition and multiplication. Can you think of a property that addition and multiplication have that string concatenation and repetition do not?

2.10. Input¶

There is a built-in function in Python for getting input from the user:

name = input("Please enter your name: ")

The user of the program can enter the name and press return. When this happens the text that has been entered is returned from the input function, and in this case assigned to the variable name.

Even if you asked the user to enter their age, you would get back a string like "17". It would be your job, as the programmer, to convert that string into a int or a float, using the int or float converter functions we saw earlier.

2.11. Composition¶

So far, we have looked at the elements of a program — variables, expressions, statements, and function calls — in isolation, without talking about how to combine them.

One of the most useful features of programming languages is their ability to take small building blocks and compose them into larger chunks.

For example, we know how to get the user to enter some input, we know how to convert the string we get into a float, we know how to write a complex expression, and we know how to print values. Let’s put these together in a small four-step program that asks the user to input a value for the radius of a circle, and then computes the area of the circle from the formula

Firstly, we’ll do the four steps one at a time:

response = input("What is your radius? ")

r = float(response)

area = 3.14159 * r**2

print("The area is ", area)

Now let’s compose the first two lines into a single line of code, and compose the second two lines into another line of code.

r = float(input("What is your radius? "))

print("The area is ", 3.14159 * r**2)

If we really wanted to be tricky, we could write it all in one statement:

print("The area is ", 3.14159*float(input("What is your radius?"))**2)

Such compact code may not be most understandable for humans, but it does illustrate how we can compose bigger chunks from our building blocks.

If you’re ever in doubt about whether to compose code or fragment it into smaller steps, try to make it as simple as you can for the human to follow. My choice would be the first case above, with four separate steps.

2.12. Glossary¶

- assignment statement

A statement that assigns a value to a name (variable). To the left of the assignment operator, =, is a name. To the right of the assignment token is an expression which is evaluated by the Python interpreter and then assigned to the name. The difference between the left and right hand sides of the assignment statement is often confusing to new programmers. In the following assignment:

n = n + 1

n plays a very different role on each side of the =. On the right it is a value and makes up part of the expression which will be evaluated by the Python interpreter before assigning it to the name on the left.

- assignment token

- = is Python’s assignment token, which should not be confused with the mathematical comparison operator using the same symbol.

- comment

- Information in a program that is meant for other programmers (or anyone reading the source code) and has no effect on the execution of the program.

- composition

- The ability to combine simple expressions and statements into compound statements and expressions in order to represent complex computations concisely.

- concatenate

- To join two strings end-to-end.

- data type

- A set of values. The type of a value determines how it can be used in expressions. So far, the types you have seen are integers (int), floating-point numbers (float), and strings (str).

- evaluate

- To simplify an expression by performing the operations in order to yield a single value.

- expression

- A combination of variables, operators, and values that represents a single result value.

- float

- A Python data type which stores floating-point numbers. Floating-point numbers are stored internally in two parts: a base and an exponent. When printed in the standard format, they look like decimal numbers. Beware of rounding errors when you use floats, and remember that they are only approximate values.

- int

- A Python data type that holds positive and negative whole numbers.

- integer division

- An operation that divides one integer by another and yields an integer. Integer division yields only the whole number of times that the numerator is divisible by the denominator and discards any remainder.

- keyword

- A reserved word that is used by the compiler to parse program; you cannot use keywords like if, def, and while as variable names.

- operand

- One of the values on which an operator operates.

- operator

- A special symbol that represents a simple computation like addition, multiplication, or string concatenation.

- rules of precedence

- The set of rules governing the order in which expressions involving multiple operators and operands are evaluated.

- state snapshot

- A graphical representation of a set of variables and the values to which they refer, taken at a particular instant during the program’s execution.

- statement

- An instruction that the Python interpreter can execute. So far we have only seen the assignment statement, but we will soon meet the import statement and the for statement.

- str

- A Python data type that holds a string of characters.

- value

- A number or string (or other things to be named later) that can be stored in a variable or computed in an expression.

- variable

- A name that refers to a value.

- variable name

- A name given to a variable. Variable names in Python consist of a sequence of letters (a..z, A..Z, and _) and digits (0..9) that begins with a letter. In best programming practice, variable names should be chosen so that they describe their use in the program, making the program self documenting.

2.13. Exercises¶

Take the sentence: All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. Store each word in a separate variable, then print out the sentence on one line using print.

Add parenthesis to the expression 6 * 1 - 2 to change its value from 4 to -6.

Place a comment before a line of code that previously worked, and record what happens when you rerun the program.

Start the Python interpreter and enter bruce + 4 at the prompt. This will give you an error:

NameError: name 'bruce' is not defined

Assign a value to bruce so that bruce + 4 evaluates to 10.

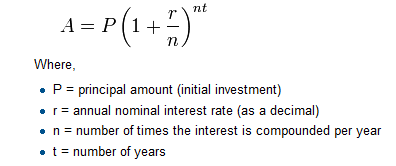

The formula for computing the final amount if one is earning compound interest is

Write a Python program that assigns the principal amount of $100 to variable p, assigns to n the value 12, and assigns to r the interest rate of 8% (as a float). Then have the program prompt the user for the number of years, t, for which the money will be compounded. Calculate and print the final amount after t years.

Tip

Remember to use type converter functions to turn the strings returned by the input function into numbers.

Make a file named ch02e06.py that contains the following

""" >>> n 42 """ # Place your solution code on the line after this one... if __name__ == '__main__': import doctest doctest.testmod()

Save the file and run it (click here to download the premade file). When you run this program, it will give you the following error:

File "ch02e06.py", line 2, in __main__ Failed example: n Exception raised: Traceback (most recent call last): File "/usr/lib/python3.2/doctest.py", line 1248, in __run compileflags, 1), test.globs) File "<doctest __main__[0]>", line 1, in <module> n NameError: name 'n' is not definedYou will become familiar with these tracebacks as you work with Python. The most important thing here is the last line, which tells you that the name n is not defined.

To define n, assign it a value by adding the following on the line immediately following the # Place your solution code on the line after this one... line in the program.

n = 11

Run the program again, and confirm that you now get this error:

File "ch02e06.py", line 2, in __main__ Failed example: n Expected: 42 Got: 11n is now defined, but our doctest is expecting its value to be 42, not 11. Fix this by changing the assignment to n to be

n = 42

When you run the program again, you should not get an error. In fact, you won’t see any output at all. If you are running your program from a command prompt, you can add -v to the end of the command to see verbose output:

$ python ch02e06.py -v Trying: n Expecting: 42 ok 1 items passed all tests: 1 tests in __main__ 1 tests in 1 items. 1 passed and 0 failed. Test passed.Note

This exercises and the exercises that follow all make use of Python’s built-in automatic testing facility call doctest. For each exercise, you will create a file that contains the following at the bottom:

if __name__ == '__main__': import doctest doctest.testmod()

The “tests” will be written at the top of the file in triple quoted strings, and will look just like interactions with the Python shell. Your task will be to make the tests pass (run without failing or returning and error).

Make a file named ch02e07.py that contains the following

""" >>> f 3.5 """ # Place your solution code on the line after this one... if __name__ == '__main__': import doctest doctest.testmod()

Make the test pass using what you learned in the previous exercise.

Create a file named ch02e08.py that contains the following

""" >>> x + y 42 >>> type(message) <class 'str'> >>> len(message) 13 """ if __name__ == '__main__': import doctest doctest.testmod()

This time there are 3 tests instead of one. You will need more than one assignment statement to make these tests pass.

From here on we will just give you the doctests for each exercise. As in the previous exercises, you will need to create a file for each one and put the three lines of Python at the bottom of the file to make the tests run.

""" >>> n + m 15 >>> n - m 5 """

You will need to create variables of the appropriate type to make these tests pass.

""" >>> type(thing1) <class 'float'> >>> type(thing2) <class 'int'> >>> type(thing3) <class 'str'> """

Remember that ** is the expontentiation operator for this one.

""" >>> x ** n 100 """

There are limitless solutions to this. Just find one that makes the tests pass.

""" >>> a + b + c 50 >>> a - c 10 """

Review string concatination before trying this one.

""" >>> s1 + s2 + s3 'Three strings were concatinated to make this string.' """