3. Strings, lists and tuples¶

3.1. Sequence data types¶

Last chapter we introduced Python’s built-in types int, float,

and str, and we stumbled upon tuple.

Integers and floats are numeric types, which means they hold numbers. We can use the numeric operators we saw last chapter with them to form numeric expressions. The Python interpreter can then evaluate these expressions to produce numeric values, making Python a very powerful calculator.

Strings, lists, and tuples are all sequence types, so called because they behave like a sequence - an ordered collection of objects.

Sequence types are qualitatively different from numeric types because they are compound data types - meaning they are made up of smaller pieces. In the case of strings, they’re made up of smaller strings, each containing one character. There is also the empty string, containing no characters at all.

In the case of lists or tuples, they are made up of elements, which are values of any Python datatype, including other lists and tuples.

Lists are enclosed in square brackets ([ and ]) and tuples in

parentheses (( and )).

A list containing no elements is called an empty list, and a tuple with no elements is an empty tuple.

[10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

["spam", "bungee", "swallow"]

(2, 4, 6, 8)

("two", "four", "six", "eight")

[("cheese", "queso"), ("red", "rojo"), ("school", "escuela")]

The first example is a list of five integers, and the next is a list of three strings. The third is a tuple containing four integers, followed by a tuple containing four strings. The last is a list containing three tuples, each of which contains a pair of strings.

Depending on what we are doing, we may want to treat a compound data type as a single thing, or we may want to access its parts. This ambiguity is useful.

Note

It is possible to drop the parentheses when specifiying a tuple, and only use a comma seperated list of values:

>>> thing = 2, 4, 6, 8

>>> type(thing)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> thing

(2, 4, 6, 8)

Also, it is required to include a comma when specifying a tuple with only one element:

>>> singleton = (2,)

>>> type(singleton)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> not_tuple = (2)

>>> type(not_tuple)

<class 'int'>

>>> empty_tuple = ()

>>> type(empty_tuple)

<class 'tuple'>

Except for the case of the empty tuple, it is really the commas, not the parentheses, that tell Python it is a tuple.

3.2. Working with the parts of a sequence¶

The sequence types share a common set of operations.

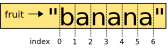

3.2.1. Indexing¶

The indexing operator ([ ]) selects a single element from a

sequence. The expression inside brackets is called the index, and must

be an integer value. The index indicates which element to select, hence its

name.

>>> fruit = "banana"

>>> fruit[1]

'a'

>>> fruits = ['apples', 'cherries', 'pears']

>>> fruits[0]

'apples'

>>> prices = (3.99, 6.00, 10.00, 5.25)

>>> prices[3]

5.25

>>> pairs = [('cheese', 'queso'), ('red', 'rojo'), ('school', 'escuela')]

>>> pairs[2]

('school', 'escuela')

The expression fruit[1] selects the character with index 1 from

fruit, and creates a new string containing just this one character,

which you may be surprised to see is 'a'.

You probably expected to see 'b', but computer scientists typically start

counting from zero, not one. Think of the index as the numbers on a ruler

measuring how many elements you have moved into the sequence from the

beginning. Both rulers and indices start at 0.

3.2.2. Length¶

Last chapter you saw the len function used to get the number of characters

in a string:

>>> len('banana')

6

With lists and tuples, len returns the number of elements in the sequence:

>>> len(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])

4

>>> len((2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12))

6

>>> pairs = [('cheese', 'queso'), ('red', 'rojo'), ('school', 'escuela')]

>>> len(pairs)

3

3.2.3. Accessing elements at the end of a sequence¶

It is common in computer programming to need to access elements at the end of

a sequence. Now that you have seen the len function, you might be tempted

to try something like this:

>>> seq = [1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0]

>>> last = seq[len(seq)] # ERROR!

That won’t work. It causes the runtime error IndexError: list index out of

range. The reason is that len(seq) returns the number of elements in the

list, 16, but there is no element at index position 16 in seq.

Since we started counting at zero, the sixteen indices are numbered 0 to 15. To get the last element, we have to subtract 1 from the length:

>>> last = seq[len(seq) - 1]

This is such a common in pattern that Python provides a short hand notation for it, negative indexing, which counts backward from the end of the sequence.

The expression seq[-1] yields the last element, seq[-2] yields the

second to last, and so on.

>>> prime_nums = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31]

>>> prime_nums[-2]

29

>>> classmates = ("Alejandro", "Ed", "Kathryn", "Presila", "Sean", "Peter")

>>> classmates[-5]

'Ed'

>>> word = "Alphabet"

>>> word[-3]

'b'

3.2.4. Traversal and the for loop¶

A lot of computations involve processing a sequence one element at a time. The most common pattern is to start at the beginning, select each element in turn, do something to it, and continue until the end. This pattern of processing is called a traversal.

Python’s for loop makes traversal easy to express:

prime_nums = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31]

for num in prime_nums:

print(num ** 2)

Note

We will discuss looping in greater detail in the next chapter. For now just note that the colon (:) at the end of the first line and the indentation on the second line are both required for this statement to be syntactically correct.

3.3. enumerate¶

As the standard for loop traverses a sequence, it assigns each value in

the sequence to the loop variable in the order it occurs in the sequence.

Sometimes it is helpful to have both the value and the index of each element.

The enumerate function gives us this:

fruits = ['apples', 'bananas', 'blueberries', 'oranges', 'mangos']

for index, fruit in enumerate(fruits):

print("The fruit, " + fruit + ", is in position " + str(index) + ".")

3.3.1. Slices¶

A subsequence of a sequence is called a slice and the operation that

extracts a subsequence is called slicing. Like with indexing, we use

square brackets ([ ]) as the slice operator, but instead of one integer

value inside we have two, seperated by a colon (:):

>>> singers = "Peter, Paul, and Mary"

>>> singers[0:5]

'Peter'

>>> singers[7:11]

'Paul'

>>> singers[17:21]

'Mary'

>>> classmates = ("Alejandro", "Ed", "Kathryn", "Presila", "Sean", "Peter")

>>> classmates[2:4]

('Kathryn', 'Presila')

The operator [n:m] returns the part of the sequence from the n’th element

to the m’th element, including the first but excluding the last. This behavior

is counter-intuitive; it makes more sense if you imagine the indices pointing

between the characters, as in the following diagram:

If you omit the first index (before the colon), the slice starts at the beginning of the string. If you omit the second index, the slice goes to the end of the string. Thus:

>>> fruit = "banana"

>>> fruit[:3]

'ban'

>>> fruit[3:]

'ana'

What do you think s[:] means? What about classmates[4:]?

Negative indexes are also allowed, so

>>> fruit[-2:]

'na'

>>> classmates[:-2]

('Alejandro', 'Ed', 'Kathryn', 'Presila')

Tip

Developing a firm understanding of how slicing works is important. Keep creating your own “experiments” with sequences and slices until you can consistently predict the result of a slicing operation before you run it.

When you slice a sequence, the resulting subsequence always has the same type as the sequence from which it was derived. This is not generally true with indexing, except in the case of strings.

>>> strange_list = [(1, 2), [1, 2], '12', 12, 12.0]

>>> print(strange_list[0], type(strange_list[0]))

(1, 2) <class 'tuple'>

>>> print(strange_list[0:1], type(strange_list[0:1]))

[(1, 2)] <class 'list'>

>>> print(strange_list[2], type(strange_list[2]))

12 <class 'str'>

>>> print(strange_list[2:3], type(strange_list[2:3]))

[12] <class 'list'>

>>>

While the elements of a list (or tuple) can be of any type, no matter how you slice it, a slice of a list is a list.

3.3.2. The in operator¶

The in operator returns whether a given element is contained in a list or

tuple:

>>> stuff = ['this', 'that', 'these', 'those']

>>> 'this' in stuff

True

>>> 'everything' in stuff

False

>>> 4 in (2, 4, 6, 8)

True

>>> 5 in (2, 4, 6, 8)

False

in works somewhat differently with strings. It evaluates to True if one

string is a substring of another:

>>> 'p' in 'apple'

True

>>> 'i' in 'apple'

False

>>> 'ap' in 'apple'

True

>>> 'pa' in 'apple'

False

Note that a string is a substring of itself, and the empty string is a substring of any other string. (Also note that computer programmers like to think about these edge cases quite carefully!)

>>> 'a' in 'a'

True

>>> 'apple' in 'apple'

True

>>> '' in 'a'

True

>>> '' in 'apple'

True

3.4. Objects and methods¶

Strings, lists, and tuples are objects, which means that they not only hold values, but have built-in behaviors called methods, that act on the values in the object.

Let’s look at some string methods in action to see how this works.

>>> 'apple'.upper()

'APPLE'

>>> 'COSATU'.lower()

'cosatu'

>>> 'rojina'.capitalize()

'Rojina'

>>> '42'.isdigit()

True

>>> 'four'.isdigit()

False

>>> ' remove_the_spaces '.strip()

'remove_the_spaces'

>>> 'Mississippi'.startswith('Miss')

True

>>> 'Aardvark'.startswith('Ant')

False

Now let’s learn to describe what we just saw. Each string in the above examples is followed by a dot operator, a method name, and a parameter list, which may be empty.

In the first example, the string 'apple' is followed by the dot operator

and then the upper() method, which has an empty parameter list. We say

that the “upper() method is invoked on the string, 'apple'.

Invoking the method causes an action to take place using the value on which the

method is invoked. The action produces a result, in this case the string value

'Apple'. We say that the upper() method returns the string

'Apple' when it is invoked on (or called on) the string 'apple'.

In the fourth example, the method isdigit() (again with an empty parameter

list) is invoked on the string '42'. Since each of the characters in the

string represents a digit, the isdigit() method returns the boolean value

True. Invoking isdigit() on 'four' produces False.

The strip() removes leading and trailing whitespace.

3.5. The dir() function and docstrings¶

The previous section introduced several of the methods of string objects. To

find all the methods that strings have, we can use Python’s built-in dir

function:

>>> dir(str)

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__doc__',

'__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__',

'__getnewargs__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__iter__', '__le__',

'__len__', '__lt__', '__mod__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__',

'__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__rmod__', '__rmul__',

'__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__',

'capitalize', 'center', 'count', 'encode', 'endswith', 'expandtabs',

'find', 'format', 'format_map', 'index', 'isalnum', 'isalpha',

'isdecimal', 'isdigit', 'isidentifier', 'islower', 'isnumeric',

'isprintable', 'isspace', 'istitle', 'isupper', 'join', 'ljust',

'lower', 'lstrip', 'maketrans', 'partition', 'replace', 'rfind',

'rindex', 'rjust', 'rpartition', 'rsplit', 'rstrip', 'split',

'splitlines', 'startswith', 'strip', 'swapcase', 'title', 'translate',

'upper', 'zfill']

>>>

We will postpone talking about the ones that begin with double underscores

(__) until later. You can find out more about each of these methods by

printing out their docstrings.

To find out what the replace method does, for example, we do this:

>>> print(str.replace.__doc__)

S.replace(old, new[, count]) -> str

Return a copy of S with all occurrences of substring

old replaced by new. If the optional argument count is

given, only the first count occurrences are replaced.

Using this information, we can try using the replace method to varify that we know how it works.

>>> 'Mississippi'.replace('i', 'X')

'MXssXssXppX'

>>> 'Mississippi'.replace('p', 'MO')

'MississiMOMOi'

>>> 'Mississippi'.replace('i', '', 2)

'Mssssippi'

The first example replaces all occurances of 'i' with 'X'. The

second replaces the single character 'p' with the two characters 'MO'.

The third example replaces the first two occurances of 'i'' with the empty

string.

3.6. count and index methods¶

There are two methods that are common to all three sequence types: count

and index. Let’s look at their docstrings to see what they do.

>>> print(str.count.__doc__)

S.count(sub[, start[, end]]) -> int

Return the number of non-overlapping occurrences of substring sub in

string S[start:end]. Optional arguments start and end are

interpreted as in slice notation.

>>> print(tuple.count.__doc__)

T.count(value) -> integer -- return number of occurrences of value

>>> print(list.count.__doc__)

L.count(value) -> integer -- return number of occurrences of value

>>> print(str.index.__doc__)

S.index(sub[, start[, end]]) -> int

Like S.find() but raise ValueError when the substring is not found.

>>> print(tuple.index.__doc__)

T.index(value, [start, [stop]]) -> integer -- return first index of value.

Raises ValueError if the value is not present.

>>> print(list.index.__doc__)

L.index(value, [start, [stop]]) -> integer -- return first index of value.

Raises ValueError if the value is not present.

We will explore these functions in the exercises.

3.7. Lists are mutable¶

Unlike strings and tuples, which are immutable objects, lists are mutable, which means we can change their elements. Using the bracket operator on the left side of an assignment, we can update one of the elements:

>>> fruit = ["banana", "apple", "quince"]

>>> fruit[0] = "pear"

>>> fruit[-1] = "orange"

>>> fruit

['pear', 'apple', 'orange']

The bracket operator applied to a list can appear anywhere in an expression.

When it appears on the left side of an assignment, it changes one of the

elements in the list, so the first element of fruit has been changed from

'banana' to 'pear', and the last from 'quince' to 'orange'. An

assignment to an element of a list is called item assignment. Item

assignment does not work for strings:

>>> my_string = 'TEST'

>>> my_string[2] = 'X'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

but it does for lists:

>>> my_list = ['T', 'E', 'S', 'T']

>>> my_list[2] = 'X'

>>> my_list

['T', 'E', 'X', 'T']

With the slice operator we can update several elements at once:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> a_list[1:3] = ['x', 'y']

>>> a_list

['a', 'x', 'y', 'd', 'e', 'f']

We can also remove elements from a list by assigning the empty list to them:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> a_list[1:3] = []

>>> a_list

['a', 'd', 'e', 'f']

And we can add elements to a list by squeezing them into an empty slice at the desired location:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'd', 'f']

>>> a_list[1:1] = ['b', 'c']

>>> a_list

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'f']

>>> a_list[4:4] = ['e']

>>> a_list

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

3.8. List deletion¶

Using slices to delete list elements can be awkward, and therefore error-prone. Python provides an alternative that is more readable.

del removes an element from a list:

>>> a = ['one', 'two', 'three']

>>> del a[1]

>>> a

['one', 'three']

As you might expect, del handles negative indices and causes a runtime

error if the index is out of range.

You can use a slice as an index for del:

>>> a_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> del a_list[1:5]

>>> a_list

['a', 'f']

As usual, slices select all the elements up to, but not including, the second index.

3.9. List methods¶

In addition to count and index, lists have several useful methods.

Since lists are mutable, these methods modify the list on which they are

invoked, rather than returning a new list.

>>> mylist = []

>>> mylist.append('this')

>>> mylist

['this']

>>> mylist.append('that')

>>> mylist

['this', 'that']

>>> mylist.insert(1, 'thing')

>>> mylist

['this', 'thing', 'that']

>>> mylist.sort()

>>> mylist

['that', 'thing', 'this']

>>> mylist.remove('thing')

>>> mylist

['that', 'this']

>>> mylist.reverse()

>>> mylist

['this', 'that']

The sort method is particularly useful, since it makes it easy to use

Python to sort data that you have put in a list.

3.10. Names and mutable values¶

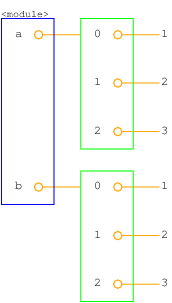

If we execute these assignment statements,

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [1, 2, 3]

we know that the names a and b will refer to a list with the numbers

1, 2, and 3. But we don’t know yet whether they point to the same

list.

There are two possible states:

or

In one case, a and b refer to two different things that have the same

value. In the second case, they refer to the same object.

We can test whether two names have the same value using ==:

>>> a == b

True

We can test whether two names refer to the same object using the is operator:

>>> a is b

False

This tells us that both a and b do not refer to the same object, and

that it is the first of the two state diagrams that describes the relationship.

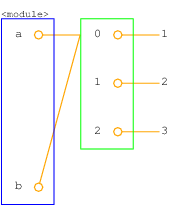

3.11. Aliasing¶

Since variables refer to objects, if we assign one variable to another, both variables refer to the same object:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a

>>> a is b

True

In this case, it is the second of the two state diagrams that describes the relationship between the variables.

Because the same list has two different names, a and b, we say that it

is aliased. Since lists are mutable, changes made with one alias affect

the other:

>>> b[0] = 5

>>> a

[5, 2, 3]

Although this behavior can be useful, it is sometimes unexpected or undesirable. In general, it is safer to avoid aliasing when you are working with mutable objects. Of course, for immutable objects, there’s no problem, since they can’t be changed after they are created.

3.12. Cloning lists¶

If we want to modify a list and also keep a copy of the original, we need to be able to make a copy of the list itself, not just the reference. This process is sometimes called cloning, to avoid the ambiguity of the word copy.

The easiest way to clone a list is to use the slice operator:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a[:]

>>> b

[1, 2, 3]

Taking any slice of a creates a new list. In this case the slice happens to

consist of the whole list.

Now we are free to make changes to b without worrying about a:

>>> b[0] = 5

>>> a

[1, 2, 3]

3.13. Nested lists¶

A nested list is a list that appears as an element in another list. In this list, the element with index 3 is a nested list:

>>> nested = ["hello", 2.0, 5, [10, 20]]

If we print nested[3], we get [10, 20]. To extract an element from the

nested list, we can proceed in two steps:

>>> elem = nested[3]

>>> elem[0]

10

Or we can combine them:

>>> nested[3][1]

20

Bracket operators evaluate from left to right, so this expression gets the

three-eth element of nested and extracts the one-eth element from it.

3.14. Strings and lists¶

Python has several tools which combine lists of strings into strings and separate strings into lists of strings.

The list command takes a sequence type as an argument and creates a list

out of its elements. When applied to a string, you get a list of characters.

>>> list("Crunchy Frog")

['C', 'r', 'u', 'n', 'c', 'h', 'y', ' ', 'F', 'r', 'o', 'g']

The split method invoked on a string and separates the string into a list

of strings, breaking it apart whenever a substring called the

delimiter occurs. The default

delimiter is whitespace, which includes spaces, tabs, and newlines.

>>> "Crunchy frog covered in dark, bittersweet chocolate".split()

['Crunchy', 'frog', 'covered', 'in', 'dark,', 'bittersweet', 'chocolate']

Here we have 'o' as the delimiter.

>>> "Crunchy frog covered in dark, bittersweet chocolate".split('o')

['Crunchy fr', 'g c', 'vered in dark, bittersweet ch', 'c', 'late']

Notice that the delimiter doesn’t appear in the list.

The join method does approximately the oposite of the split method.

It takes a list of strings as an argument and returns a string of all the

list elements joined together.

>>> ' '. join(['crunchy', 'raw', 'unboned', 'real', 'dead', 'frog'])

'crunchy raw unboned real dead frog'

The string value on which the join method is invoked acts as a separator

that gets placed between each element in the list in the returned string.

>>> '**'.join(['crunchy', 'raw', 'unboned', 'real', 'dead', 'frog'])

'crunchy**raw**unboned**real**dead**frog'

The separator can also be the empty string.

>>> ''.join(['crunchy', 'raw', 'unboned', 'real', 'dead', 'frog'])

'crunchyrawunbonedrealdeadfrog'

3.15. Tuple assignment¶

Once in a while, it is useful to swap the values of two variables. With

conventional assignment statements, we have to use a temporary variable. For

example, to swap a and b:

temp = a

a = b

b = temp

If we have to do this often, this approach becomes cumbersome. Python provides a form of tuple assignment that solves this problem neatly:

a, b = b, a

The left side is a tuple of variables; the right side is a tuple of values. Each value is assigned to its respective variable. All the expressions on the right side are evaluated before any of the assignments. This feature makes tuple assignment quite versatile.

Naturally, the number of variables on the left and the number of values on the right have to be the same:

>>> a, b, c, d = 1, 2, 3

ValueError: need more than 3 values to unpack

3.16. Boolean values¶

We will now look at a new type of value - boolean values - named after the British mathematician, George Boole. He created the mathematics we call Boolean algebra, which is the basis of all modern computer arithmetic.

Note

It is a computer’s ability to alter its flow of execution depending on whether a boolean value is true or false that makes a general purpose computer more than just a calculator.

There are only two boolean values, True and False.

>>> type(True)

<class 'bool'>

>>> type(False)

<class 'bool'>

Capitalization is important, since true and false are not boolean

values in Python.:

>>> type(true)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<interactive input>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'true' is not defined

3.17. Boolean expressions¶

A boolean expression is an expression that evaluates to a boolean value.

The operator == compares two values and produces a boolean value:

>>> 5 == 5

True

>>> 5 == 6

False

In the first statement, the two operands are equal, so the expression evaluates

to True; in the second statement, 5 is not equal to 6, so we get False.

The == operator is one of six common comparison operators; the others

are:

x != y # x is not equal to y

x > y # x is greater than y

x < y # x is less than y

x >= y # x is greater than or equal to y

x <= y # x is less than or equal to y

Although these operations are probably familiar to you, the Python symbols are

different from the mathematical symbols. A common error is to use a single

equal sign (=) instead of a double equal sign (==). Remember that =

is an assignment operator and == is a comparison operator. Also, there

is no such thing as =< or =>.

3.18. Logical operators¶

There are three logical operators: and, or, and not. The

semantics (meaning) of these operators is similar to their meaning in English.

For example, x > 0 and x < 10 is true only if x is greater than 0 and

at the same time, x is less than 10.

n % 2 == 0 or n % 3 == 0 is true if either of the conditions is true,

that is, if the number is divisible by 2 or divisible by 3.

Finally, the not operator negates a boolean expression, so not (x > y)

is true if (x > y) is false, that is, if x is less than or equal to

y.

>>> 5 > 4 and 8 == 2 * 4

True

>>> True and False

False

>>> False or True

True

3.19. Short-circuit evaluation¶

Boolean expressions in Python use short-circuit evaluation, which means

only the first argument of an and or or expression is evaluated when

its value is suffient to determine the value of the entire expression.

This can be quite useful in preventing runtime errors. Imagine you want

check if the fifth number in a tuple of integers named numbers is even.

The following expression will work:

>>> numbers = (5, 11, 13, 24)

>>> numbers[4] % 2 == 0

unless of course there are not 5 elements in numbers, in which case you

will get:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: tuple index out of range

>>>

Short-circuit evaluation makes it possible to avoid this problem.

>>> len(numbers) >= 5 and numbers[4] % 2 == 0

False

Since the left hand side of this and expression is false, Python does not

need to evaluate the right hand side to determine that the whole expression is

false. Since it uses short-circuit evaluation, it does not, and the runtime

error is avoided.

3.20. “Truthiness”¶

All Python values have a “truthiness” or “falsiness” which means they can be used in places requiring a boolean. For the numeric and sequence types we have seen thus far, truthiness is defined as follows:

- numberic types

Values equal to 0 are false, all others are true.

- sequence types

Empty sequences are false, non-empty sequences are true.

Combining this notion of truthiness with an understanding of short-circuit evaluation makes it possible to understand what Python is doing in the following expressions:

>>> 'A' and 'apples'

'apples'

>>> '' and 'apples'

''

>>> '' or [5, 6]

[5, 6]

>>> ('a', 'b', 'c') or [5, 6]

('a', 'b', 'c')

3.21. Glossary¶

- aliases¶

Multiple variables that contain references to the same object.

- boolean value¶

There are exactly two boolean values:

TrueandFalse. Boolean values result when a boolean expression is evaluated by the Python interepreter. They have typebool.- boolean expression¶

An expression that is either true or false.

- clone¶

To create a new object that has the same value as an existing object. Copying a reference to an object creates an alias but doesn’t clone the object.

- comparison operator¶

One of the operators that compares two values:

==,!=,>,<,>=, and<=.- compound data type¶

A data type in which the values are made up of components, or elements, that are themselves values.

- element¶

One of the parts that make up a sequence type (string, list, or tuple). Elements have a value and an index. The value is accessed by using the index operator (

[*index*]) on the sequence.- immutable data type¶

A data type which cannot be modified. Assignments to elements or slices of immutable types cause a runtime error.

- index¶

A variable or value used to select a member of an ordered collection, such as a character from a string, or an element from a list or tuple.

- logical operator¶

One of the operators that combines boolean expressions:

and,or, andnot.- mutable data type¶

A data type which can be modified. All mutable types are compound types. Lists and dictionaries are mutable data types; strings and tuples are not.

- nested list¶

A list that is an element of another list.

- slice¶

A part of a string (substring) specified by a range of indices. More generally, a subsequence of any sequence type in Python can be created using the slice operator (

sequence[start:stop]).- step size¶

The interval between successive elements of a linear sequence. The third (and optional argument) to the

rangefunction is called the step size. If not specified, it defaults to 1.- traverse¶

To iterate through the elements of a collection, performing a similar operation on each.

- tuple¶

A data type that contains a sequence of elements of any type, like a list, but is immutable. Tuples can be used wherever an immutable type is required, such as a key in a dictionary (see next chapter).

- tuple assignment¶

An assignment to all of the elements in a tuple using a single assignment statement. Tuple assignment occurs in parallel rather than in sequence, making it useful for swapping values.