|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A vector is a set of values where each value is identified by a number (called an index). An pstring is similar to a vector, since it is made up of an indexed set of characters. The nice thing about vectors is that they can be made up of any type of element, including basic types like ints and doubles, and user-defined types like Point and Time.

The vector type that appears on the AP exam is called pvector. In order to use it, you have to include the header file pvector.h; again, the details of how to do that depend on your programming environment.

You can create a vector the same way you create other variable types:

pvector<int> count;The type that makes up the vector appears in angle brackets (< and >). The first line creates a vector of integers named count; the second creates a vector of doubles. Although these statements are legal, they are not very useful because they create vectors that have no elements (their length is zero). It is more common to specify the length of the vector in parentheses:

pvector<int> count (4);The syntax here is a little odd; it looks like a combination of a variable declarations and a function call. In fact, that's exactly what it is. The function we are invoking is an pvector constructor. A constructor is a special function that creates new objects and initializes their instance variables. In this case, the constructor takes a single argument, which is the size of the new vector.

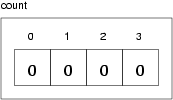

The following figure shows how vectors are represented in state diagrams:

The large numbers inside the boxes are the elements of the vector. The small numbers outside the boxes are the indices used to identify each box. When you allocate a new vector, the elements are not initialized. They could contain any values.

There is another constructor for pvectors that takes two parameters; the second is a "fill value," the value that will be assigned to each of the elements.

pvector<int> count (4, 0);This statement creates a vector of four elements and initializes all of them to zero.

The [] operator reads and writes the elements of a vector in much the same way it accesses the characters in an pstring. As with pstrings, the indices start at zero, so count[0] refers to the "zeroeth" element of the vector, and count[1] refers to the "oneth" element. You can use the [] operator anywhere in an expression:

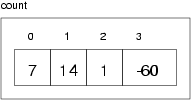

count[0] = 7;All of these are legal assignment statements. Here is the effect of this code fragment:

Since elements of this vector are numbered from 0 to 3, there is no element with the index 4. It is a common error to go beyond the bounds of a vector, which causes a run-time error. The program outputs an error message like "Illegal vector index", and then quits.

You can use any expression as an index, as long as it has type int. One of the most common ways to index a vector is with a loop variable. For example:

int i = 0;This while loop counts from 0 to 4; when the loop variable i is 4, the condition fails and the loop terminates. Thus, the body of the loop is only executed when i is 0, 1, 2 and 3.

Each time through the loop we use i as an index into the vector, outputting the ith element. This type of vector traversal is very common. Vectors and loops go together like fava beans and a nice Chianti.

There is one more constructor for pvectors, which is called a copy constructor because it takes one pvector as an argument and creates a new vector that is the same size, with the same elements.

pvector<int> copy (count);Although this syntax is legal, it is almost never used for pvectors because there is a better alternative:

pvector<int> copy = count;The = operator works on pvectors in pretty much the way you would expect.

The loops we have written so far have a number of elements in common. All of them start by initializing a variable; they have a test, or condition, that depends on that variable; and inside the loop they do something to that variable, like increment it.

This type of loop is so common that there is an alternate loop statement, called for, that expresses it more concisely. The general syntax looks like this:

for (INITIALIZER; CONDITION; INCREMENTOR) {This statement is exactly equivalent to

INITIALIZER;except that it is more concise and, since it puts all the loop-related statements in one place, it is easier to read. For example:

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {is equivalent to

int i = 0;There are only a couple of functions you can invoke on an pvector. One of them is very useful, though: length. Not surprisingly, it returns the length of the vector (the number of elements).

It is a good idea to use this value as the upper bound of a loop, rather than a constant. That way, if the size of the vector changes, you won't have to go through the program changing all the loops; they will work correctly for any size vector.

for (int i = 0; i < count.length(); i++) {The last time the body of the loop gets executed, the value of i is count.length() - 1, which is the index of the last element. When i is equal to count.length(), the condition fails and the body is not executed, which is a good thing, since it would cause a run-time error.

Most computer programs do the same thing every time they are executed, so they are said to be deterministic. Usually, determinism is a good thing, since we expect the same calculation to yield the same result. For some applications, though, we would like the computer to be unpredictable. Games are an obvious example.

Making a program truly nondeterministic turns out to be not so easy, but there are ways to make it at least seem nondeterministic. One of them is to generate {pseudorandom} numbers and use them to determine the outcome of the program. Pseudorandom numbers are not truly random in the mathematical sense, but for our purposes, they will do.

C++ provides a function called random that generates pseudorandom numbers. It is declared in the header file stdlib.h, which contains a variety of "standard library" functions, hence the name.

The return value from random is an integer between 0 and RAND_MAX, where RAND_MAX is a large number (about 2 billion on my computer) also defined in the header file. Each time you call random you get a different randomly-generated number. To see a sample, run this loop:

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {On my machine I got the following output:

1804289383You will probably get something similar, but different, on yours.

Of course, we don't always want to work with gigantic integers. More often we want to generate integers between 0 and some upper bound. A simple way to do that is with the modulus operator. For example:

int x = random ();Since y is the remainder when x is divided by upperBound, the only possible values for y are between 0 and upperBound - 1, including both end points. Keep in mind, though, that y will never be equal to upperBound.

It is also frequently useful to generate random floating-point values. A common way to do that is by dividing by RAND_MAX. For example:

int x = random ();This code sets y to a random value between 0.0 and 1.0, including both end points. As an exercise, you might want to think about how to generate a random floating-point value in a given range; for example, between 100.0 and 200.0.

The numbers generated by random are supposed to be distributed uniformly. That means that each value in the range should be equally likely. If we count the number of times each value appears, it should be roughly the same for all values, provided that we generate a large number of values.

In the next few sections, we will write programs that generate a sequence of random numbers and check whether this property holds true.

The first step is to generate a large number of random values and store them in a vector. By "large number," of course, I mean 20. It's always a good idea to start with a manageable number, to help with debugging, and then increase it later.

The following function takes a single argument, the size of the vector. It allocates a new vector of ints, and fills it with random values between 0 and upperBound-1.

pvector<int> randomVector (int n, int upperBound) {The return type is pvector<int>, which means that this function returns a vector of integers. To test this function, it is convenient to have a function that outputs the contents of a vector.

void printVector (const pvector<int>& vec) {Notice that it is legal to pass pvectors by reference. In fact it is quite common, since it makes it unnecessary to copy the vector. Since printVector does not modify the vector, we declare the parameter const.

The following code generates a vector and outputs it:

int numValues = 20;On my machine the output is

3 6 7 5 3 5 6 2 9 1 2 7 0 9 3 6 0 6 2 6which is pretty random-looking. Your results may differ.

If these numbers are really random, we expect each digit to appear the same number of times---twice each. In fact, the number 6 appears five times, and the numbers 4 and 8 never appear at all.

Do these results mean the values are not really uniform? It's hard to tell. With so few values, the chances are slim that we would get exactly what we expect. But as the number of values increases, the outcome should be more predictable.

To test this theory, we'll write some programs that count the number of times each value appears, and then see what happens when we increase numValues.

A good approach to problems like this is to think of simple functions that are easy to write, and that might turn out to be useful. Then you can combine them into a solution. This approach is sometimes called bottom-up design. Of course, it is not easy to know ahead of time which functions are likely to be useful, but as you gain experience you will have a better idea.

Also, it is not always obvious what sort of things are easy to write, but a good approach is to look for subproblems that fit a pattern you have seen before.

Back in Section 7.9 we looked at a loop that traversed a string and counted the number of times a given letter appeared. You can think of this program as an example of a pattern called "traverse and count." The elements of this pattern are:

In this case, I have a function in mind called howMany that counts the number of elements in a vector that equal a given value. The parameters are the vector and the integer value we are looking for. The return value is the number of times the value appears.

int howMany (const pvector<int>& vec, int value) {howMany only counts the occurrences of a particular value, and we are interested in seeing how many times each value appears. We can solve that problem with a loop:

int numValues = 20;Notice that it is legal to declare a variable inside a for statement. This syntax is sometimes convenient, but you should be aware that a variable declared inside a loop only exists inside the loop. If you try to refer to i later, you will get a compiler error.

This code uses the loop variable as an argument to howMany, in order to check each value between 0 and 9, in order. The result is:

value howManyAgain, it is hard to tell if the digits are really appearing equally often. If we increase numValues to 100,000 we get the following:

value howManyIn each case, the number of appearances is within about 1% of the expected value (10,000), so we conclude that the random numbers are probably uniform.

It is often useful to take the data from the previous tables and store them for later access, rather than just print them. What we need is a way to store 10 integers. We could create 10 integer variables with names like howManyOnes, howManyTwos, etc. But that would require a lot of typing, and it would be a real pain later if we decided to change the range of values.

A better solution is to use a vector with length 10. That way we can create all ten storage locations at once and we can access them using indices, rather than ten different names. Here's how:

int numValues = 100000;I called the vector histogram because that's a statistical term for a vector of numbers that counts the number of appearances of a range of values.

The tricky thing here is that I am using the loop variable in two different ways. First, it is an argument to howMany, specifying which value I am interested in. Second, it is an index into the histogram, specifying which location I should store the result in.

Although this code works, it is not as efficient as it could be. Every time it calls howMany, it traverses the entire vector. In this example we have to traverse the vector ten times!

It would be better to make a single pass through the vector. For each value in the vector we could find the corresponding counter and increment it. In other words, we can use the value from the vector as an index into the histogram. Here's what that looks like:

pvector<int> histogram (upperBound, 0);The first line initializes the elements of the histogram to zeroes. That way, when we use the increment operator (++) inside the loop, we know we are starting from zero. Forgetting to initialize counters is a common error.

As an exercise, encapsulate this code in a function called histogram that takes a vector and the range of values in the vector (in this case 0 through 10), and that returns a histogram of the values in the vector.

If you have run the code in this chapter a few times, you might have noticed that you are getting the same "random" values every time. That's not very random!

One of the properties of pseudorandom number generators is that if they start from the same place they will generate the same sequence of values. The starting place is called a seed; by default, C++ uses the same seed every time you run the program.

While you are debugging, it is often helpful to see the same sequence over and over. That way, when you make a change to the program you can compare the output before and after the change.

If you want to choose a different seed for the random number generator, you can use the srand function. It takes a single argument, which is an integer between 0 and RAND_MAX.

For many applications, like games, you want to see a different random sequence every time the program runs. A common way to do that is to use a library function like gettimeofday to generate something reasonably unpredictable and unrepeatable, like the number of milliseconds since the last second tick, and use that number as a seed. The details of how to do that depend on your development environment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|